Flow-Induced Phase Transitions

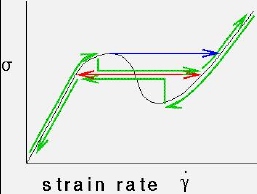

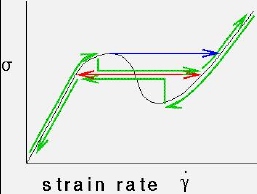

The

internal

structure of complex fluids, such as liquid crystals, surfactant solutions,

or polymers, is rearranged and altered in flow. This shows up in measurements

of the stress as a function of strain rate, which is a boring straight

line for a simple fluid. In strong enough flows transitions can be induced

between phases, which gives rise to a non-monatonic stress-strain relation,

as shown here. The important question to understand is how the system `knows'

when to jump from the low to high shear branches.

The

internal

structure of complex fluids, such as liquid crystals, surfactant solutions,

or polymers, is rearranged and altered in flow. This shows up in measurements

of the stress as a function of strain rate, which is a boring straight

line for a simple fluid. In strong enough flows transitions can be induced

between phases, which gives rise to a non-monatonic stress-strain relation,

as shown here. The important question to understand is how the system `knows'

when to jump from the low to high shear branches.

Does it pick the red branch all the time

(which looks suspiciously like the Maxwell construction), does it jump

at the limit of stability, or does it take

a hysteretic path, depending on how fast the

system parameters are changed? Experiments seem to indicate that it takes

the hysteretic path, and steady states fall

on a plateau. It is tempting to treat such

transitions in the language of equilibrium phase transitions, which can

be fruitful as well as dangerous.

The curve shown here is just one of many topologically possible curves.

The isotropic-nematic transition in liquid crystalline systems has curves

which are multi-valued in both stress and strain rate, and experiments

have indicated the existence of systems which have a transition at either

a specified strain rate, or at a specified stress.

But wait, there's more. This is just one example. Fluids can also phase

separate into shear-thickening phases. There's a whole zoo out there waiting

to be tamed (or fed).

The

figure on the right demonstrates the different possibilities for flow-induced

phase transitions. Either the two phases can have the same shear stress,

as on the left; or the two phases can have the same strain rate (specified

by the counter-rotating cylinders) as on the right. In the common stress

case (left) the strain rate varies in the two phases, while in the common

strain rate case (right) the shear stress is different in the two

phases. Hence the analog of

field and density variables in

equilibrum, such as pressure and density respectively, depends on the geometry

of the phase separation. The two lower rows show the possible rheological

signatures for shear-thinning (middle row) and shear-thickening (top row)

transitions, for the two geometries. The flat or vertical solid green lines

show the composite rheological signature if the

concentrations of

the coexisting phases are the same; while the curved dotted green lines

show what can happen if the concentrations in the coexisting phases differ.

The deviation from vertical (common strain rate) or horizontal (common

stress) depends on the details of the non-equilibrium phase diagram.

The

figure on the right demonstrates the different possibilities for flow-induced

phase transitions. Either the two phases can have the same shear stress,

as on the left; or the two phases can have the same strain rate (specified

by the counter-rotating cylinders) as on the right. In the common stress

case (left) the strain rate varies in the two phases, while in the common

strain rate case (right) the shear stress is different in the two

phases. Hence the analog of

field and density variables in

equilibrum, such as pressure and density respectively, depends on the geometry

of the phase separation. The two lower rows show the possible rheological

signatures for shear-thinning (middle row) and shear-thickening (top row)

transitions, for the two geometries. The flat or vertical solid green lines

show the composite rheological signature if the

concentrations of

the coexisting phases are the same; while the curved dotted green lines

show what can happen if the concentrations in the coexisting phases differ.

The deviation from vertical (common strain rate) or horizontal (common

stress) depends on the details of the non-equilibrium phase diagram.

The

figure on the right demonstrates the different possibilities for flow-induced

phase transitions. Either the two phases can have the same shear stress,

as on the left; or the two phases can have the same strain rate (specified

by the counter-rotating cylinders) as on the right. In the common stress

case (left) the strain rate varies in the two phases, while in the common

strain rate case (right) the shear stress is different in the two

phases. Hence the analog of

field and density variables in

equilibrum, such as pressure and density respectively, depends on the geometry

of the phase separation. The two lower rows show the possible rheological

signatures for shear-thinning (middle row) and shear-thickening (top row)

transitions, for the two geometries. The flat or vertical solid green lines

show the composite rheological signature if the

concentrations of

the coexisting phases are the same; while the curved dotted green lines

show what can happen if the concentrations in the coexisting phases differ.

The deviation from vertical (common strain rate) or horizontal (common

stress) depends on the details of the non-equilibrium phase diagram.

The

figure on the right demonstrates the different possibilities for flow-induced

phase transitions. Either the two phases can have the same shear stress,

as on the left; or the two phases can have the same strain rate (specified

by the counter-rotating cylinders) as on the right. In the common stress

case (left) the strain rate varies in the two phases, while in the common

strain rate case (right) the shear stress is different in the two

phases. Hence the analog of

field and density variables in

equilibrum, such as pressure and density respectively, depends on the geometry

of the phase separation. The two lower rows show the possible rheological

signatures for shear-thinning (middle row) and shear-thickening (top row)

transitions, for the two geometries. The flat or vertical solid green lines

show the composite rheological signature if the

concentrations of

the coexisting phases are the same; while the curved dotted green lines

show what can happen if the concentrations in the coexisting phases differ.

The deviation from vertical (common strain rate) or horizontal (common

stress) depends on the details of the non-equilibrium phase diagram.

The

internal

structure of complex fluids, such as liquid crystals, surfactant solutions,

or polymers, is rearranged and altered in flow. This shows up in measurements

of the stress as a function of strain rate, which is a boring straight

line for a simple fluid. In strong enough flows transitions can be induced

between phases, which gives rise to a non-monatonic stress-strain relation,

as shown here. The important question to understand is how the system `knows'

when to jump from the low to high shear branches.

The

internal

structure of complex fluids, such as liquid crystals, surfactant solutions,

or polymers, is rearranged and altered in flow. This shows up in measurements

of the stress as a function of strain rate, which is a boring straight

line for a simple fluid. In strong enough flows transitions can be induced

between phases, which gives rise to a non-monatonic stress-strain relation,

as shown here. The important question to understand is how the system `knows'

when to jump from the low to high shear branches.